Can I start by saying I hate the title ‘study skills’ (I really want to write that as ‘skillz’, followed by that clicky hand gesture, you know the one where you hold your thumb and middle finger together and make that sound…) so if anyone can suggest a better name, give me shout!

I’m not saying that to be controversial, but I really think the idea of teaching our students to be studious is watered down by calling it ‘study skills‘. Like it’s a series of discrete things someone can do to achieve academic success. But it’s really not. Being an effective student is much, much more than that. It is a series of ingrained habits, developed and perfected over a series of years, learning from mistakes, successes and time spent; it is disciplined, practised and consistent, and students really need to know that. They should be explicitly taught how to study, how to develop good habits and so too do parents.

Again, including parents in this learning process is not something I say to be controversial, but to highlight the influence they have on students’ study habits. Knowing why independent study is important, how it can be used effectively, and how to avoid inefficiency is essential. A consistent message is key.

I have blogged previously on explicitly teaching metacognition in lessons, and study skills are an extension of this practice, to further develop our students as independent learners, beyond the classroom.

Being completely categorical that becoming an independent learner is not about revision, the preconceived idea of the thing you do the night before test, hoping for the best. This is a clear set of habits effective learners have, that they do daily, weekly, regardless of forthcoming tests, they do it to learn.

Sharing Evidence

‘Start with why’ (Simon Sinek).

For students, staff and parents we share the evidence to support study skills strategies:

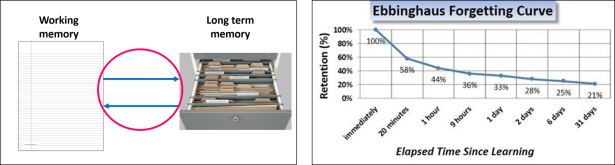

Memory

Using the model of working and long term memory, in an accessible format, then exploring the relationship between the two, is the initial ‘why’. Clearly stating that, for them to remember things there has to be a transfer into the long-term memory, and back again, repeatedly, until this is automatic. Doing this in conjunction with the forgetting curve really emphasises the purpose behind the structure and strategies of effective study habits.

Motivation

For some students, this will feel completely alien to them, that they are learning to learn. Moreover, thinking hard is not an easy thing to do, if it was, we would all be doing it, and we’re not! There are a multitude of reasons for this, how the brain is ‘designed’, extrinsic influences and motivators. So, sharing evidence about motivation with students, and explaining that they need to feel success to feel motivated, is the second ‘why’:

“… the effect of achievement on self-concept is stronger than the effect of self-concept on achievement” (Mujis & Reynolds, 2011)

Study habits & anxiety

As educated professionals we would agree that developing effective study habits is the cornerstone to academic success, however, they provide much more advantage than helping secure academic outcomes. For many, if not most students, studying, learning and exam preparation is a stressful time and we are seeing an ever increasing incidence in anxiety in students. Studies have shown that test anxiety and study habits have a strong correlation. In this study from 2017, undergraduate students, who we may consider more expert learners than those in our classrooms, were surveyed on their study habits (which were assessed for effectiveness) and their test anxiety:

“Multivariate analysis of variance indicated that study habits have a significant effect on test anxiety and academic achievement. The findings revealed that students having effective study habits experience low level of test anxiety and perform better academically than students having ineffective study habits.”

(Numan & Hasan, 2017)

Even in expert learners, anxiety can be correlated to ineffective study habits, which is a really stark message for our students. Explicitly linking this for them,explaining that avoiding anxiety around tests and exams can be something in their control, is the final ‘why’. For many students, empowering them in this way generates a huge buy-in, knowing that they have complete ownership over it, can be intrinsically motivating.

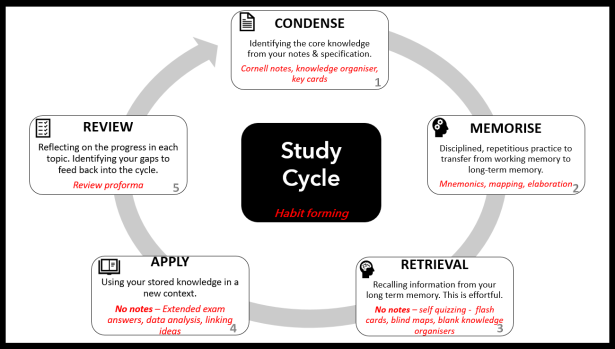

Embedding habitual practice

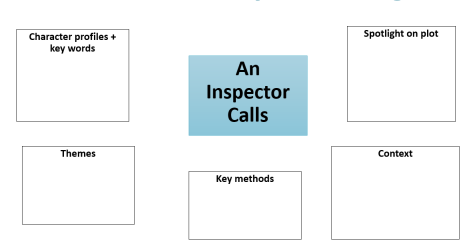

Following the why, sharing a common language for study is crucial. This is shared with students through assemblies (and then embedded in lessons), staff (to embed into lessons) and parents (to embed at home). Now, this may seem ‘Like it’s a series of discrete things someone can do to achieve academic success’, which it probably is, the point being, it is a structure upon which students can practice the habits of successful learning, providing them a scaffold upon which to build.

This model has been adapted from Didcot Girls’ School.

NB: This is not intended to be a lesson structure, or SoW sequence, but something tangible students can use to structure their own independent study, away from lessons. To ensure their study sessions are efficient, and not time consuming with little reward (think of the student who spends hours upon hours writing and re-writing notes, reading and re-reading them, to still not be able to remember the major causes of WW1).

Emphasis should be placed on the importance of the cyclic nature of study, it is not a one off event, but a process that needs to be replicated many times, and should be revisited and refined to secure it.

Students are also guided to track their study for a subject or topic, have they condensed, memorised, etc, for a topic section? They also use the tracker to highlight any issues or effectiveness with a particular topic and strategy. ![]()

Condensing

What do you mean when you want a student to condense their notes? This is inextricably linked in the sharing of powerful knowledge (discussed so eloquently in @Rosalindphys blog on the work of Michael Young) with students. They need to know what is core to their understanding, of a topic.

The core is the essential knowledge we want them to take away, the facts, the dates, the narrative, however, in lessons we often use ‘Hinterland’ to add context, hooks and relevance to that core knowledge. Adam Boxer talks about this beautifully here.

So how we model this is imperative. Modelling the condensing of core knowledge must not be reductive to the knowledge itself, therefore, carefully selecting the content we include in our knowledge organisers is key. At my school, not all departments have begun work with knowledge organisers, therefore, we train students in using Cornell notes in their independent learning.

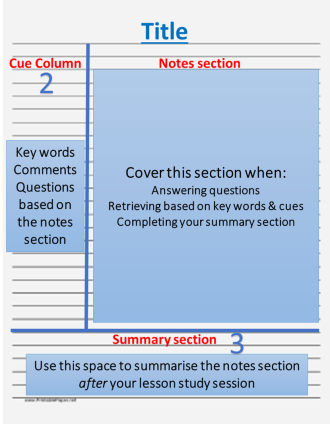

Using Cornell note taking

Cornell notes are becoming increasingly popular, and for good reason. They give a clear structure, and emphasise the importance of core knowledge, questioning, and using retrieval for long term memory.

Modelling their use has been really valuable, in its basic structure, how to use it as a method for condensing and subsequent retrieval practice.

Basic structure

How to use during a study session

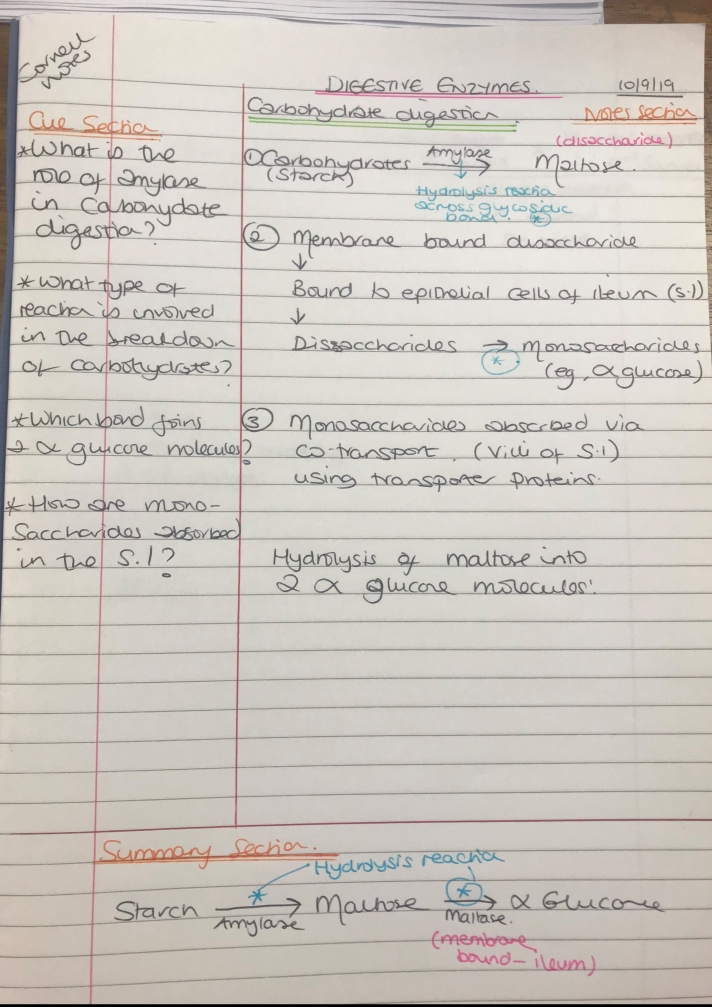

A modelled set of Cornell notes (year 12 biology.)

Memorising

To emphasise that this a verb, something students need to do, cannot be overstated. Knowledge is not going to magically deposit itself in their long-term memory, without them doing something. Explicit emphasis is placed on the repetitious and disciplined nature of memorisation.

Retrieval

Using retrieval practice has become a bedrock of many people’s practice, and rightly so. Encouraging the effortful recall from long-term memory, and defeating the forgetting curve is a transformative concept. This has been employed in our lessons, curriculum and in the language we use with students. They are well versed in its use, and why it’s useful. However, emphasising the personal responsibility, in utilising retrieval practice as part of their own study, has been important, therefore, sharing evidence behind memory was powerful for them. Tom Sherrington has shared 10 ideas for retrieval practice here, which can be adapted for lesson use or independent learning.

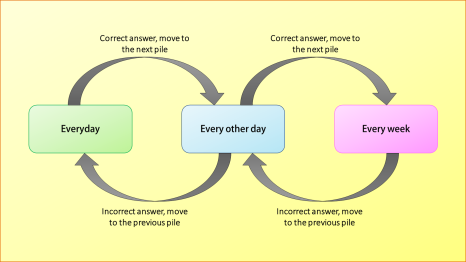

Flash cards (Letiner method)

Students love a flash card! Talk to them about ‘revision’ and the first suggestion is flash cards. I’ve seen students with piles upon piles of flash cards, when asked what they do with them they say “Well, I make them”… “But what do you do with them” … silence…. or “I keep them together so the corners don’t turn curl up”.

So, we spend time modelling the Leitner Method (proposed in the 1970’s by journalist Sebastian Leitner).

Students have their stack of flash cards, they self quiz, verbally, on paper or with a partner; they file their answers into piles of ‘know’ and ‘don’t know’. If they ‘know’ something, they then quiz every other day, then every week (if they continue to ‘know’ it) or if they ‘don’t know’ they would quiz each day, until they do. The time intervals of retrieval are not hard and fast, but the ‘know’ and ‘don’t know’ are key to identifying their developmental areas.

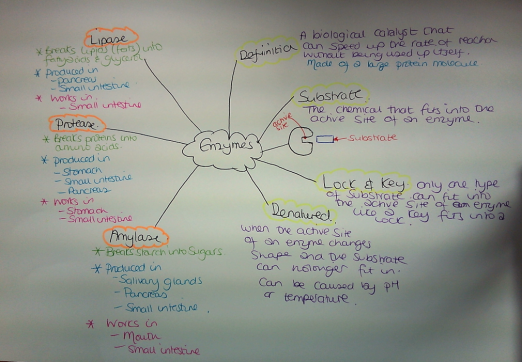

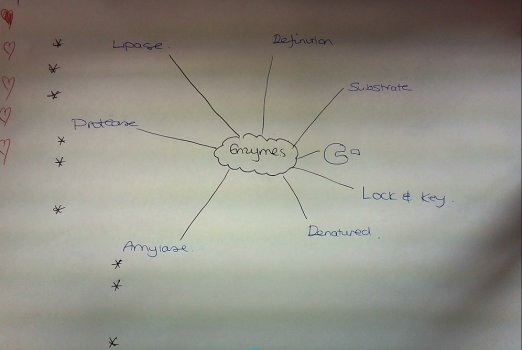

Mind mapping & blind mapping

In lessons, mind maps are modelled, how to select core information to include on them and where to make appropriate links between or within concepts.

The the blind map is modelled, where students are given a skeleton structure of the mind map, which stem titles, or a diagram, to scaffold their retrieval, they then complete as much of it as possible from memory. Initially, I recommend they use a ‘lives’ system, so if they need to check back on notes, they may ‘lose a life’, recording this on their blind map to record how much they can actually remember. I would recommend they remove this scaffold as their practice develops.

Blank knowledge organisers

Where subjects have knowledge organisers, students are taught to self quiz using them. As part of their retrieval practice, they can use a blank knowledge to retrieve core knowledge, to structure their ideas into themes and identify aspects of a topic or unit that need further development.

Apply

This involves taking their core knowledge and applying it to new contexts, or extended responses and is a further development of their retrieval.Key stage 4 & 5 students have access to exam board past paper questions, and essay titles (or sections thereof) for appropriate subjects. The study cycle itself is entrenched in developing effective independent learners, for learning’s sake, however, it would be remiss to ignore the inevitability of exams in year 11 and year 13. These are the key to future opportunity for many students, therefore, giving them appropriate disciplined knowledge of the exams is essential.

Time is spent in lessons modelling exam technique, how exams are structured, looking at the literacy of exams, and what command words might mean for each subject. This is done in a context driven way, not just a list of command words and definitions, which are ultimately glued in books and never see the light of day again.

Alongside this, utilising mark schemes is taught, in order to aid students’ self-assessment of exam answers in their independent learning. Significant time is spent teaching this to avoid (or minimise) Dunning-Kruger effect.

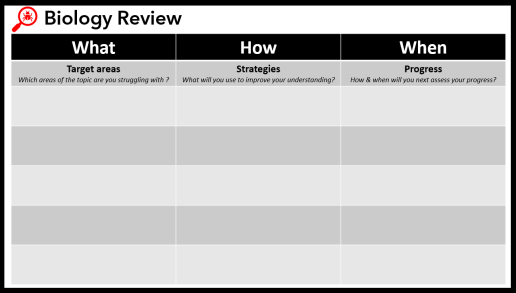

Review

The conclusion of the study cycle is the review section, where students do exactly what it says on the tin. They are guided to spend to reflecting on what they have done in a specific topic, where they have been successful, and where they need to develop. Using the previous stages of the cycle they are able to identify the thing they ‘know’ and what they ‘don’t know’ and how well they have been able to apply it (comparing their work to a mark scheme or exemplar answer).

The how and the when are utilised to identify where they will feed this topic area back into the study cycle, which strategies would be effective, or more effective, and a time commitment to doing it.

This is for everyone

In education we have long banded around the terms associated with ability, making a distinction between those who are and are not able. But what does that even mean? Able to learn? We are all able to learn.

“When we label students by ability, we limit their potential to learn”

Being explicitly clear that everyone is capable of forming effective study habits is a message carried to students, staff and parents. And this is never more important. They have the right to be independent from us as teachers, their current knowledge and the ties of their situation. Being an effective, independent learner is not the preserve of the elite, academically, socially, financially, but an entitlement of all of our students.

Great post. Do you mind if I link to it in some of my blogs?

plutoniumscience.com/category/for-students/revision/

LikeLike

No, that’s fine. Thanks,

LikeLike

This is a great post. Going to use the ideas and processes with my classes as we have a real issue in English where pupil’s don’t think they can revise for the subject.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jenni, I am really pleased it of some use to you. Louise.

LikeLike